Archie Bunker’s Chair – Media Images and Social Realities of Irish America in the Chaos Sixties and Seventies

By Tony Bucher

The genesis of this talk was a story published in Salon online magazine on St. Patrick’s Day 2014 by Executive Editor Andrew O’Hehir entitled “How did my fellow Irish-Americans get so disgusting?” O’Hehir presents the image of braying, asinine reactionary media figures like Sean Hannity and Bill O’Reilly and their ilk, joined with plastic Paddy bars, schlocky New Age Celtic mysticism, and an intrinsically racist past as the main features of a faded and degenerate Irish American identity.

Here’s O’Hehir’s money quote: “Irishness is a nonspecific global brand of pseudo-old pubs, watered-down Guinness, “Celtic” tattoos and vague New Age spirituality, designed to make white people feel faintly cool without doing any of the hard work of actually learning anything. On the other, it’s Bill O’Reilly, Sean Hannity, Pat Buchanan and Rep. Peter King, Long Island’s longtime Republican congressman (and IRA supporter), consistently representing the most stereotypical grade of racist, xenophobic, small-minded, right-wing Irish-American intolerance. When you think of the face of white rage in America, it belongs to a red-faced Irish dude on Fox News.” He presents this smattering of impressions with little grounding in real history and no essential connection with his subjects and their lived experience.

Here’s O’Hehir’s money quote: “Irishness is a nonspecific global brand of pseudo-old pubs, watered-down Guinness, “Celtic” tattoos and vague New Age spirituality, designed to make white people feel faintly cool without doing any of the hard work of actually learning anything. On the other, it’s Bill O’Reilly, Sean Hannity, Pat Buchanan and Rep. Peter King, Long Island’s longtime Republican congressman (and IRA supporter), consistently representing the most stereotypical grade of racist, xenophobic, small-minded, right-wing Irish-American intolerance. When you think of the face of white rage in America, it belongs to a red-faced Irish dude on Fox News.” He presents this smattering of impressions with little grounding in real history and no essential connection with his subjects and their lived experience.

Historian Van Gosse more recently published a more nuanced and well-informed version of essentially the same argument with similar points of reference:

“Just as they used to play an outsize role in the Democratic Party’s apparatus, and in organized labor, putative Irishmen are now the face of the hard Right. Once the biggest names, faces, and voices on television were Huntley and Brinkley, Cronkite, Murrow, even John Chancellor and Dan Rather, all sober, serious Americans—and all Protestants too. Now we have angry loudmouths with names like O’Reilly, Hannity, Buchanan, and, lurking back there with his Cheshire smile, the dissolute but scary Bannon. Yet no one has noticed this obvious fact, and the sheer lack of attention may be the most important thing about it. Why has the ascent of a bunch of people who in an earlier period might have been called Micks drawn no notice at all?”

He does present a valuable question, a challenge really: “What happened to Irish America, that closed, intense world I know mainly from movies and books? How could I make sense of its drying up and blowing away, unmourned?” Both cite Noel Ignatiev’s unfortunate How the Irish Became White as the key scholarly resource, whose central theme is that the great mass of downtrodden Irish immigrants in the 19th century made a collective decision, at some point and by some collective means, to embrace “whiteness” and strive to join with the dominant racial group, and as a collective entity to actively take part in the oppression of non-white peoples in America.

Is this it for Irish America – that our entire experience in America, with our ubiquitous and oftentimes idiosyncratic presence, can be distilled by this marginally researched and deeply condescending line of argument? The tone and content of this argument is: ‘the decline of Irish America, we are well to be done with this pestilence…’

This perspective completely fails to recognize the thoughts, feelings, experiences, and motivations of the varied faces of the ethnic community that is the actual subject of this material (and to what other ethnic or racial minority would these statements be deemed remotely acceptable?)

This perspective completely fails to recognize the thoughts, feelings, experiences, and motivations of the varied faces of the ethnic community that is the actual subject of this material (and to what other ethnic or racial minority would these statements be deemed remotely acceptable?)

There is a certain critical, faux-objective distance and lack of empathy in play which registers clearly with older forms of anti-Irish Catholic prejudice. The willingness to assign collective blame to an entire ethnic group for the sins of some of its members is a hallmark of racial prejudice with a long heritage in the United States. And yet the notion has remarkable tenacity among the progressive thinking classes.

This stirred my anger, quite naturally, but also my curiosity: How did this notion of the retrograde reactionary as the primary exemplar of the Irish American become fixed in popular and political consciousness in the first place, given the wealth and diversity of historical experience available to us through the news, literature, and popular culture of the past 170 or so years since the Famine and the flood tide of immigration? Why does this ethnic minority alone merit this particular kind of scorn?

Berkeley writer Ishmael Reed offered a direct counterpoint to this jaundiced perspective on Irish Americana in a 2008 story titled "The Black-Irish Thing" (full text below): "Although there are many progressive Irish Americans like (San Francisco author Danny) Cassidy, the media profile of Irish America lies somewhere between shrill talk-show hosts, who yell and interrupt their guests or a snarling resentful Archie Bunker type, or Bernard McQuirk ,whose comment about the Rutgers basketball team led to Don Imus’s firing, or a pugnacious Pat Buchanan who believes that it was Grant who surrendered at Appomattox.

In the movies it’s “Dirty Harry Callahan” who violates the constitutional rights of suspects. There seems to be no place for a Pat Goggins of the San Francisco United Irish Cultural Center, or authors Bob Callahan and Dan Cassidy, who have worked for decades to heal whatever divisions exist between African Americans and Irish Americans."

For my own answers I was immediately drawn to the late 1960's and the 1970's, when O’Hehir and I came of age in Berkeley, California - a time and place where the schism between the New Left and the ethnic working and middle classes first appeared, and the present lines of political demarcation, and much of the language of the political divisions, were first drawn. Immersion in memories of the culture, personalities, and politics of my Seventies adolescence drew me much further down a fascinating line of inquiry than even I had expected.

All in the Family

It was during that turbulent era that powerful and largely unflattering images of the Irish American community were fixed in the news and popular culture. Certain Irish Americans came to personify the forces of reaction in American society in a period of intense social activism and racial, inter-generational, and class conflict.

Irish Americans were in fact in the forefront of embattled white ethnic working class reaction in New York City, Boston and Chicago, and even halcyon San Francisco.

A closer examination reveals a vastly more complex reality. There were important class divisions, barely acknowledged by the liberal managerial classes, between those at the bottom, often left to their own devices in the inner city, and those residing comfortably remote from the urban morass in the middle class and upper middle class suburbs.

Irish Americans were ubiquitous in instrumental roles on both the left and the right, in both reactionary and progressive movements, with many innovative and outlandish figures in the world of popular culture as well.

Ladies and Gentlemen, the Bronx is Burning

Irish Americans were in fact in the forefront of embattled white ethnic working class reaction in New York City, Boston and Chicago, and even halcyon San Francisco.

A closer examination reveals a vastly more complex reality. There were important class divisions, barely acknowledged by the liberal managerial classes, between those at the bottom, often left to their own devices in the inner city, and those residing comfortably remote from the urban morass in the middle class and upper middle class suburbs.

Irish Americans were ubiquitous in instrumental roles on both the left and the right, in both reactionary and progressive movements, with many innovative and outlandish figures in the world of popular culture as well.

Ladies and Gentlemen, the Bronx is Burning

This discussion takes us back to an era that astonishes us today with the shocking levels of social disorder and rampant physical decay in our great cities.

These were commonly accepted images of New York City after the collapse of the manufacturing economy, suburban white flight, and chaos in the streets.

In a sense, the now barely-remembered New York Blackout of 1977 was a kind of coup de grace on the failing urban order, even as the seeds of quite outlandish new culture were taking root in the environment of social decay.

During this period, in many cities, the voice of the streets was often most ably expressed in a tabloid newspaper by an Irish American journalist. Brooklyn's Pete Hamill was known for chronicling the litany of resentments expressed in the taverns of his working class Irish neighborhood in Park Slope, as the social order in the city nearly collapsed and large areas were devastated by rampant street crime, rioting, and arson.

Hamill opened an essay titled “The Lawless Decades” referring to the American 1960s and 1970s with this: “The American slide into urban barbarism has yet to find its Gibbon. But someday a great historian must try to answer the first persistent question: What happened to us in the last third of the twentieth century?” Much can be gleaned from the news and entertainment media of the era.

Journalist Maureen Dezell, author of Coming Into Clover, a personal chronicle of Irish America, says of Irish Americans in the urban crisis of the late Sixties and Seventies – “we were kind of in the wrong place at the wrong time”, as those left behind as the cities teetered on the edge of disaster became the focus, in many cases, of upper middle class liberal ire and derision. She goes on to identify a strain of anti-Irish Catholic sentiment as a “safe mask for what we don’t like about the white working class”.

The white working class of that era was most distinctively portrayed by actor Carroll O’Connor, playing Archie Bunker in the television situation comedy All in the Family.

The white working class of that era was most distinctively portrayed by actor Carroll O’Connor, playing Archie Bunker in the television situation comedy All in the Family.

For years much of America followed the travails of blustery, bumbling Archie Bunker in All in the Family, which ran from 1971 to 1979. It was an American adaptation of the BBC show Till Death Do Us Part with a cast that included Sally Struthers, Rob Reiner, Jean Stapleton, and Carroll O’Connor as the patriarch of a working class family in a fading white ethnic Queens neighborhood. Archie in his humble upholstered chair saw himself as the master of his domain, even as the forces of change drew inexorably within the flimsy walls of the Bunker home. Noisy arguments issued weekly on every imaginable issue and presented the turmoil of the era in stark candor often shocking to audiences then and certainly since.

The Bunkers ostensibly represented the remnants of the generic Anglo-American working class, but Archie was played unmistakably New York Irish by Queens native Carroll O'Connor - who consciously modeled his Archie on Jackie Gleason and James Cagney and the range of real life “Archies” he saw growing up in his Queens neighborhood. The director and driving creative force of the show, Norman Lear, was asked “why not have an Irish Archie – with that face?" - but he made a conscious decision to not associate Archie with any particular ethnic group, but rather to cast Archie as an American every-man to represent regressive attitudes common in the general population.

O’Connor, himself a rather tender-hearted Catholic liberal intellectual, was personally deeply troubled by the enormous popularity of his bigoted Archie, the product of his own genius talent, and even recorded a special public service television ad to counsel against embracing the attitudes of his character. In a recent documentary, Lear said that, as a “liberal Irish Catholic”, O’Connor struggled with playing Archie throughout his tenure on the show.

Likewise, Peter Boyle was said to have been so disturbed by the popularity of the grotesque satire he created in the title character for Joe, a 1970 film about a hardhat construction worker who kills hippies for sport, that he quit acting altogether for two years.

Boyle also played the villainous, duplicitous bartender in The Friends of Eddie Coyle, a film based on the brilliant minimalist noir by George Higgins set in the dreary fringes of the Boston criminal underworld, with a downcast Robert Mitchum playing the misbegotten Irish American hoodlum on a one way path to the grave (The role was originally cast with noir great Lawrence Tierney, who had some troubles with law enforcement at the time which prevented him from working);

The Godfather film brought Sterling Hayden's brutal and corrupt Captain Mark McCluskey to life, before Michael Corleone shot him in the Luna restaurant in the Bronx ;

Gene Hackman (replacing journalist Jimmy Breslin) played NYPD Detective Jimmy Popeye Doyle in The French Connection, based on the exploits of real life NYPD Detective Eddie Egan, himself cast in a bit part in the film - 'Doyle is bad news, but a good cop';

Diane Keaton played the victim of a shouting, dysfunctional New York rowhouse family in the dark and deeply disturbing true crime drama Looking for Mr. Goodbar;

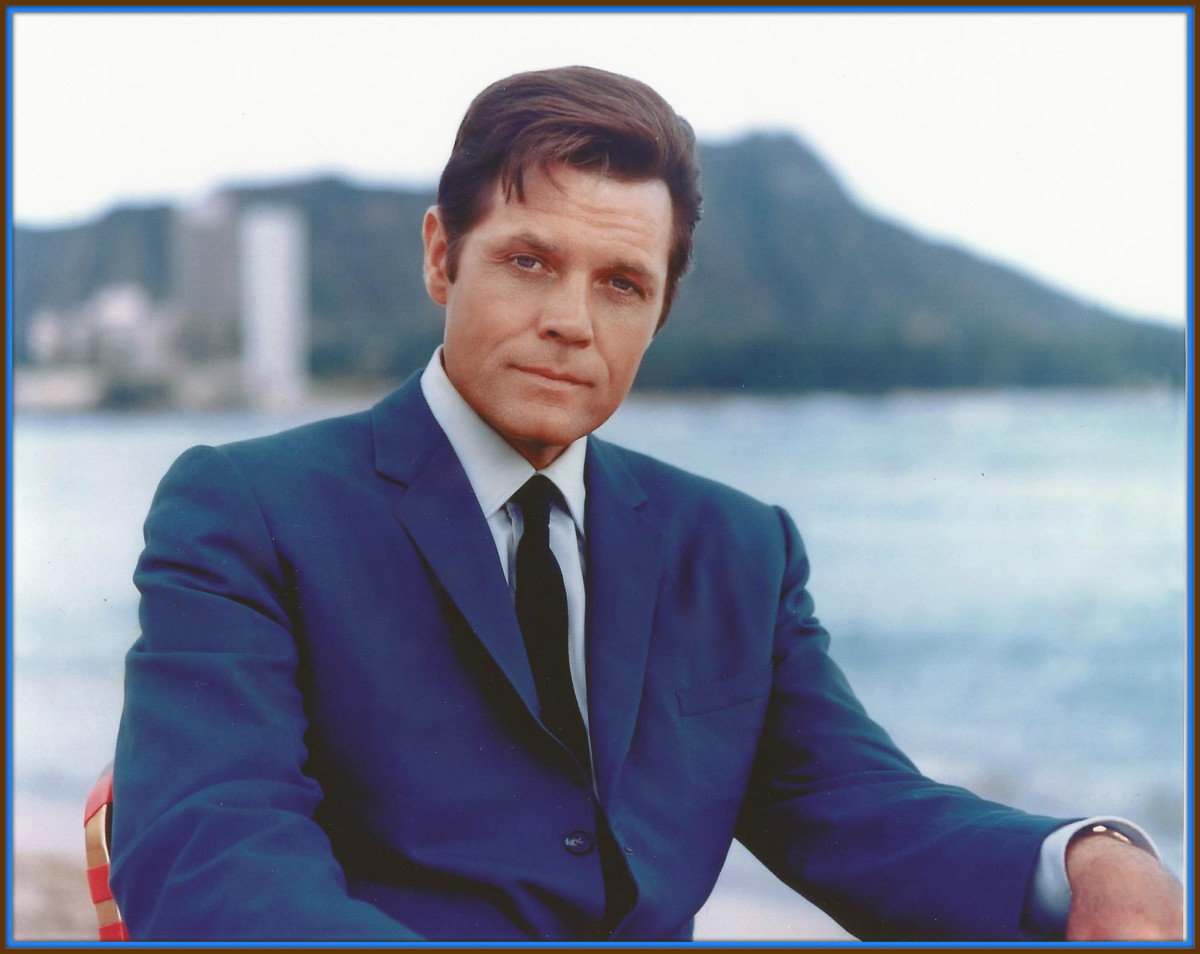

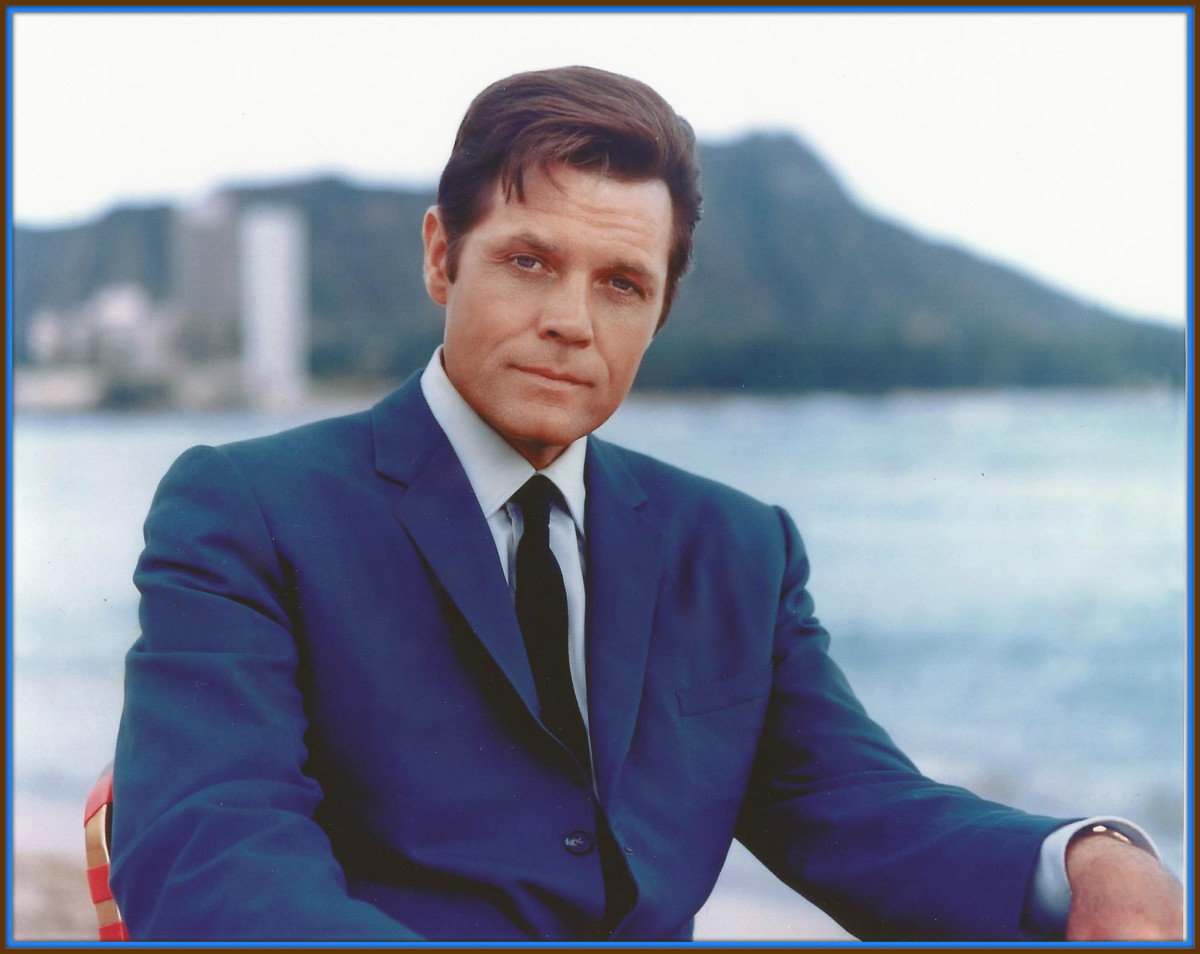

John Joseph Patrick Ryan, better known as Jack Lord, played the prince of the Honolulu PD - the aloof and cerebral Lieutenant Steve McGarrett - on television's Hawaii 50.

Kathy Moriarty appeared as the precocious Bronx teen bride Vicki LaMotta in Raging Bull;

In Ragtime, based on E.L. Doctorow's eponymous 1976 novel, Coalhouse Walker, Jr. is detained by the racist members of the Emerald Isle Volunteer Fire House, led by fire chief Willie Conklin (played by Kenneth McMillan), setting off a chain of tragic events that ultimately leads to Walker's destruction by order of James Cagney's Police Commissioner;

Clint Eastwood presented Dirty Harry Callahan as an avenging angel in the era of rampant crime and disorder;

Dirty Harry Callahan was supposedly modeled on real-life San Francisco Police Lieutenant Jack Webb, who knew the streets of the City's notorious Tenderloin district better than any man alive. Unlike Dirty Harry or Clint Eastwood, Webb's politics ran to US Democratic and Irish Republican.

Boyle also played the villainous, duplicitous bartender in The Friends of Eddie Coyle, a film based on the brilliant minimalist noir by George Higgins set in the dreary fringes of the Boston criminal underworld, with a downcast Robert Mitchum playing the misbegotten Irish American hoodlum on a one way path to the grave (The role was originally cast with noir great Lawrence Tierney, who had some troubles with law enforcement at the time which prevented him from working);

The Godfather film brought Sterling Hayden's brutal and corrupt Captain Mark McCluskey to life, before Michael Corleone shot him in the Luna restaurant in the Bronx ;

Gene Hackman (replacing journalist Jimmy Breslin) played NYPD Detective Jimmy Popeye Doyle in The French Connection, based on the exploits of real life NYPD Detective Eddie Egan, himself cast in a bit part in the film - 'Doyle is bad news, but a good cop';

Diane Keaton played the victim of a shouting, dysfunctional New York rowhouse family in the dark and deeply disturbing true crime drama Looking for Mr. Goodbar;

John Joseph Patrick Ryan, better known as Jack Lord, played the prince of the Honolulu PD - the aloof and cerebral Lieutenant Steve McGarrett - on television's Hawaii 50.

Kathy Moriarty appeared as the precocious Bronx teen bride Vicki LaMotta in Raging Bull;

In Ragtime, based on E.L. Doctorow's eponymous 1976 novel, Coalhouse Walker, Jr. is detained by the racist members of the Emerald Isle Volunteer Fire House, led by fire chief Willie Conklin (played by Kenneth McMillan), setting off a chain of tragic events that ultimately leads to Walker's destruction by order of James Cagney's Police Commissioner;

Clint Eastwood presented Dirty Harry Callahan as an avenging angel in the era of rampant crime and disorder;

Dirty Harry Callahan was supposedly modeled on real-life San Francisco Police Lieutenant Jack Webb, who knew the streets of the City's notorious Tenderloin district better than any man alive. Unlike Dirty Harry or Clint Eastwood, Webb's politics ran to US Democratic and Irish Republican.

Many of these stories featured struggling characters of the working and lower middle class caught up in forces beyond their comprehension or control, in socially realistic portrayals of the tensions and fault lines of the era - that made for bad living but gripping entertainment.

In the real world Irish Americans retained an essential feel and connection with the streets that was like DNA. Mid-century Irish American journalists chronicled daily life in the big city – few more celebrated than Jimmy Breslin, a burly Queens native tabloid writer with varied interests in politics, new journalism, and the stories of ordinary people in the dirty, rough streets of New York.

Journalist Jim Rutenberg eulogized Breslin in the New York Times: "The reason I fell in love with newspapers — the printed kind — was because of the great columnists of the New York City tabloids, whose bylines hit the sidewalks like anvils when the delivery trucks dropped their bundled papers off at newsstands overnight: Kempton, McAlary, Duggan, Hamill, Dwyer, Daly, Collins, Gonzalez. You wanted to be them (or, at least, I did).

Journalist Jim Rutenberg eulogized Breslin in the New York Times: "The reason I fell in love with newspapers — the printed kind — was because of the great columnists of the New York City tabloids, whose bylines hit the sidewalks like anvils when the delivery trucks dropped their bundled papers off at newsstands overnight: Kempton, McAlary, Duggan, Hamill, Dwyer, Daly, Collins, Gonzalez. You wanted to be them (or, at least, I did).

Their columns lionized the working stiff, gave cops their due when they were heroic — yet showed them no mercy when they were on the take or being abusive — and shook City Hall until the corruption and hypocrisy spilled out onto their crisply printed pages.

But no name quite defined the genre like that of Breslin. He became known nationally for his blunt Noo Yawk persona, somebody whose word was as honest as it was direct — for the mix of people he brought to life, Runyon-worthy characters like Vincent (the Chin) Gigante; Gothamesque killers like the Son of Sam, David Berkowitz; and noble everymen like Clifton Pollard, who dug President John F. Kennedy’s grave. He did important work that made his city better, like the columns that showed what it was like to have AIDS and that exposed torture in a Queens station house, which won him a Pulitzer Prize in 1986.”

The Dawn of the Age of Aquarius

The Dawn of the Age of Aquarius

The dozen years between 1968 and 1980 were far from being universally dark and turbulent; it was also an era of remarkable cultural ferment. A whole range of Irish Americans played leading roles in the waves of change that ran through the politics and popular culture. One of the brightest lights was trailblazing psychedelic pioneer (or con man, depending on your perspective) Dr. Timothy Leary, whose exhortation to “Tune In, Turn On, and Drop Out” was adopted as a generational manifesto.

There was the brilliant, iconoclastic, self-promoting street bard and activist Emmett Grogan, who invented the anarchist ethic of hippiedom, wrote a self-inflating account of his life and personal philosophy, and ended up dead of a heroin overdose on a Brooklyn subway car. Grogan was a founder of the Diggers in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury, who took their name from the English Diggers, a radical movement opposed to feudalism, the Church of England and the British Crown.

The Diggers combined street theater, direct action, and art happenings with the goal of creating a Free City, where everything was free for the taking, led by the slogans "Do your own thing" and "Today is the first day of the rest of your life".

Yippie Abby Hoffman wrote this about Grogan: "The San Francisco Diggers combined Dada street theater with the revolutionary politics of free. Slum-alley saints, they lit up the period by spreading the poetry of love and anarchy with broad strokes of artistic genius. Their free store, communications network of instant offset survival poetry, along with an Indian-inspired consciousness, was the original white light of the era. Emmett Grogan was the hippie warrior par excellence. He was also a junkie, a maniac, a gifted actor, a rebel hero, ...and above all a pain in the ass to all his friends..."

Tom Hayden led the Students for a Democratic Society and authored the Port Huron Statement, the seminal manifesto of New Left dissent from the political mainstream, in the early 1960s. He was known as an astute and sometimes paranoid player, the Nixon of the Left, who in later years maintained an active role in conventional politics through his terms in California state elective office.

He came relatively late in life to realize a powerful connection with his Irish American heritage. In his book Irish on the Inside he addressed the cultural amnesia that he saw in the baffling indifference of his parents' generation to their own history in America, and his own belated discovery of the rather fascinating political history of the Hayden and Garity families in the US.

People Who Died, Died

People Who Died, Died

In the 1970s countercultural domain, compelling voices emerged from the gritty streets of New York City.

Upper Manhattan nurtured the comic genius of George Carlin, who provided subversive 1970s adolescents with the six words you can’t say on television, and set himself apart as an astute and contrarian social critic and avowed socialist.

Carlin, ever the comic pioneer, hosted the very first episode of Saturday Night Live.

Jim Carroll, bard of the underclass streets of Manhattan, came of age in Inwood in the 1960s, descended from three generations of Irish bartenders. His most popular work was the autobiographical Basketball Diaries (1978), which chronicled his double life as a star student and basketball player who also happened to be a junkie, hustling gay men in the toilets at Times Square subway station to support his drug habit.

The great Anne Meara purveyed her brand of sarcastic humor in partnership with her husband Jerry Stiller, their union symbolizing the frequent pairing of the Jews and the Irish in entertainment. She was seen in later years, ever herself, playing dramatic roles including an embattled inner city schoolteacher in the Fame film, and much later the outer borough ethnic mom Mary Brady in Sex and the City.

National Lampoon magazine chief Michael O'Donoghue wrote and appeared in the very first sketch ever aired on Saturday Night Live, which along with the Lampoon came to thoroughly define the emergent comic sensibilities of the era.

Deeply subversive, often dark, beyond risqué, O’Donoghue was a core influence at the Lampoon, and wrote many of the most memorable sketches for SNL, where he garnered two Emmy awards.

A friend described O'Donoghue's sensibilities as being, to put it mildly, somewhat out of the mainstream: "Someone gave him an original painting by serial killer John Wayne Gacy...that sort of described his ethos...His childhood home was filled with books, classical music, and Mrs. O'Donoghue's frequently nasty sense of humor, which her only son gladly claimed as his birthright. He was beyond dark or black Irish; he was macabre".

The Lampoon/SNL scene nurtured the careers of Bill Murray, Jane Curtin, Catherine O’Hara, and Brian Doyle Murray and created a genre that dominates comedy to this day.

1968 and Beyond

In the turbulent political environment of the era, Chicago Mayor Richard Daley, known in Chicago's black community as Pharaoh, massively powerful, brutal, and implacable, came to personify reactionary resistance to the forces of political and social change in the violence he unleashed in the streets of his city during the 1968 Democratic convention.

In that same year the South Bronx native Police Sergeant Joseph MacNamara confronted student protesters in the Columbia University riots. MacNamara, who would later rise to become chief of police of Kansas City and then San Jose and a widely respected progressive law enforcement scholar, commanded officers during the worst violence at Columbia.

In an interview with me a dozen years ago, he described his view of the conflict - through the lens of his experience as a cop in the roughest streets of West Harlem - a vast, densely inhabited, garbage-strewn ghetto sprawling immediately below the leafy, pristine Columbia campus. His view was that "The police came from the working class and they looked at these students as the future leaders of America" with frank admiration for their station in life, yet "here they were behaving like animals, and dangerous".

These were cops who went on daily patrol in Harlem on their own with no communications and no vest, on streets completely abandoned by the rest of America, in a precinct that saw an astonishing 100 murders a year in a single square mile. "Crime was out of control", he said. These were “cops who had just handled shootings and stabbings in Harlem and were being baited by rich, snotty kids” at Columbia.

The students seemed to excel at provoking the police, and after submitting to days of scornful, vulgar taunts and defecation flung at them, the street cops exacted their revenge in a battle which has since become lore.

Boston

The open street battles in the Boston school desegregation crisis of 1974 to 1976 presented similarly repellent images of open conflict on the streets of South Boston and downtown.

For those more closely involved in the Boston struggle, Maureen Dezell says, “the Boston busing crisis was an Irish family feud” waged between the poor and immobile in the housing projects of Southie, and the upper middle class professional class long since fled to comfortable suburbs, who administered desegregation, in a situation exacerbated by some of the most venal political figures in Boston history, all of which abetted the pestilential influence of organized crime.

Journalist Martin Nolan recalls Councilman John G. Kerrigan as an especially troublesome racist agitator, who manipulated the intelligent and basically well-intentioned Louise Day Hicks, public face of the opposition to school busing.

For those more closely involved in the Boston struggle, Maureen Dezell says, “the Boston busing crisis was an Irish family feud” waged between the poor and immobile in the housing projects of Southie, and the upper middle class professional class long since fled to comfortable suburbs, who administered desegregation, in a situation exacerbated by some of the most venal political figures in Boston history, all of which abetted the pestilential influence of organized crime.

Journalist Martin Nolan recalls Councilman John G. Kerrigan as an especially troublesome racist agitator, who manipulated the intelligent and basically well-intentioned Louise Day Hicks, public face of the opposition to school busing.

About these years, author Michael Patrick MacDonald, one of a family of 8 children raised in the housing projects, wrote: “Among the rarely discussed facts about my neighborhood was that white South Boston High School had the highest number of students on welfare in any school, citywide”, and that per-student funding was lowest in the city.

“Once Southie exploded, Garrity’s plan would appear justified to liberals all over the country. National news crews descended on the neighborhood to focus only on the scenes of inexcusable racist violence, without examining any of the equally important class manipulation at play in a plan that would send rightfully aggrieved African American students into a school that, in spite of its predominant complexion, was as bad if not worse than the one they came from.”

In proudly Irish American Southie, as helicopters hovered overhead, as police marched through the streets in riot gear, as snipers stood on our rooftops, many people equated busing with the British occupation of the north of Ireland. Indeed, the State Board of Education, which devised the busing plan that Garrity approved, was not only stacked with WASP names like “Saltonstall”—but also, Charles Glenn, who wrote the plan, was descended from Ulster Protestants.

In a show of solidarity and that famously Irish insistence to “stand one’s ground,” many South Boston public school students—the neighborhood’s poorest, those who could not escape to private or parochial schools—boycotted and eventually dropped out. A generation was lost to that chaos.”

Gangster Whitey Bulger reaped the benefits of the turmoil, running huge quantities of cocaine into the community that ruined lives and killed scores.

Gangster Whitey Bulger reaped the benefits of the turmoil, running huge quantities of cocaine into the community that ruined lives and killed scores.

Even easygoing San Francisco saw extreme reactionary violence in the 1978 murders of Supervisor Harvey Milk and Mayor George Moscone by the conservative working class assassin Dan White, who deployed the infamous Twinkies defense to serve a three year sentence for the double murder, and who upon release found himself unable to bear the shame, and so committed suicide in his own garage to the strains of 'The Fields of Athenry' in his tape deck.

Critical reporting on the whole saga was provided by famed and highly eccentric Irish American journalist Warren Hinckle - who ascribed the Dan White murders to seething racial and homophobic resentment in some quarters of the City.

Hinckle wrote: “Dan White's San Francisco is the unpicturesque southeastern flatlands where the city meets the slurbs. This is the home of Joe Six-pack. The area has the most savings accounts...fewer newspapers delivered, and the lowest voter turnout. The neighborhoods, heavily Catholic, ethnically Maltese to Samoan, hard-working and no-nonsense- are the last reservoir of the blue-collar ethic in a romantic city lately tilting towards narcissism. People out here still call chicken breasts "white meat" because they don't wish to mention the anatomy.”

(SF Mayor) George Moscone ordered the cops to handle the gays with lavender gloves. This was an order not enthusiastically received among the rank and file. The liberal mayor also appointed a reformist-minded chief from outside the department...the first outsider in half a century to head the clique-ridden, Irish Catholic-dominated San Francisco Police Department, which was operated mainly on the buddy system: promotions could hinge on which parish you belonged to and other Irish tribal rites and departmental policy was often settled in conversations on the church steps after Sunday mass. The new chief's attempts to modernize the department...were met with Russian-front type resistance from the troops. The most bitter opposition came from the...POA, a union with some of the cultish overtones of an Orange lodge, which powerhoused the notorious Police strike of 1975 in which many cops destroyed police cars, slashed tires, and waved guns and otherwise behaved like goons. Even before he got to the jail and received a welcome fit for Lindbergh, ex-cop Dan White was the political hero and great white hope of the POA."

Both Dan White and Warren Hinckle were self-consciously and intrinsically Irish American San Franciscans, albeit representing very different strains in that close-knit and idiosyncratic community.

Hinckle's flamboyant account is directly contradicted by Dan White's longtime aide, Roy Sloan, who gave his own account of those events in an article published by the SF Weekly newspaper 30 years later: "Sloan, who is gay, says no aspect of White's crimes can be put in a positive light. But he believes White has frequently been falsely portrayed. In the book Gayslayer! by Warren Hinckle...and in countless newspaper and magazine stories, White has been characterized as a religious zealot, a homophobe, and a hired assassin for the San Francisco Police Department, the Catholic Church, or both. These characterizations are ridiculous, Sloan says, but the one he believes is most unfair is that Dan White killed Harvey Milk because of his homosexuality." With the passage of time, accounts have settled and memories faded. There are still aspects of the story that will never be fully, publicly settled.

Another key player of the turbulent era in law enforcement was San Francisco's own Police Chief Thomas Cahill, whose name adorns the aging and decrepit San Francisco Hall of Justice, and whose experience provides some counterpoint to Warren Hinckle’s jaundiced view of the SFPD.

Hinckle's flamboyant account is directly contradicted by Dan White's longtime aide, Roy Sloan, who gave his own account of those events in an article published by the SF Weekly newspaper 30 years later: "Sloan, who is gay, says no aspect of White's crimes can be put in a positive light. But he believes White has frequently been falsely portrayed. In the book Gayslayer! by Warren Hinckle...and in countless newspaper and magazine stories, White has been characterized as a religious zealot, a homophobe, and a hired assassin for the San Francisco Police Department, the Catholic Church, or both. These characterizations are ridiculous, Sloan says, but the one he believes is most unfair is that Dan White killed Harvey Milk because of his homosexuality." With the passage of time, accounts have settled and memories faded. There are still aspects of the story that will never be fully, publicly settled.

Another key player of the turbulent era in law enforcement was San Francisco's own Police Chief Thomas Cahill, whose name adorns the aging and decrepit San Francisco Hall of Justice, and whose experience provides some counterpoint to Warren Hinckle’s jaundiced view of the SFPD.

Cahill, a man still held in reverence by those who served under him, was one of the more celebrated law enforcement officials in the United States in the 1960s, known for his probity, professionalism, and his essential openness and availability to all of his constituencies. (This philosophy of governance was carried forward by his aide and future San Francisco Police Chief and Mayor Frank Jordan as well.)

His son related an anecdote from 1963, about the day Chief Cahill appeared at the podium in front of San Francisco City Hall before a large and very tense and emotionally raw gathering of San Francisco’s black community in the aftermath of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham, Alabama. Cahill took the stage to publicly donate his own funds towards the recovery. It was precisely that gesture and more like it that earned him the goodwill of San Francisco's black community, and that enabled him to seek a negotiated peace of sorts as the turmoil of the era came to a head in 1969.

Here is an image from the press conference he held after the culmination of successful negotiations with the Black Panthers in April of 1969 to keep avenues of discussion open between leadership of the Police Department and the black community.

Here is an image from the press conference he held after the culmination of successful negotiations with the Black Panthers in April of 1969 to keep avenues of discussion open between leadership of the Police Department and the black community.

Cahill was eulogized at his 2002 funeral by SPFD Chief Napoleon Sanders and Mayor Willie Brown as the public official and trusted honest broker most responsible for saving San Francisco from destructive civil unrest in the late 1960s.

The Power Brokers

This discussion inevitably leads to a broader examination of the nature of Irish power in America in the 19th and 20th centuries, a process which must begin at the apex of that power, personified by the Kennedy brothers. For mid-century Irish America everything begins, and perhaps ends, with the Kennedys.

This discussion inevitably leads to a broader examination of the nature of Irish power in America in the 19th and 20th centuries, a process which must begin at the apex of that power, personified by the Kennedy brothers. For mid-century Irish America everything begins, and perhaps ends, with the Kennedys.

Their success was seen by many as the culmination of Irish America’s long process of becoming fully American. Larry Tye describes the arc that brought RFK from a Joe McCarthy acolyte to a deeply committed social activist in the space of 10 years, influenced by the socialist thinker Michael Harrington who shone a light for the first time on real poverty in America.

Through his suffering he developed a profound empathy for disadvantaged members of American society, which drew him into powerful connection with minority and working class communities that perhaps we have not seen since. Radical civil rights leader Sonny Carson, head of the Brooklyn CORE..."had seen the heads turn when Bobby Kennedy walked into the church: "Man it was like the Pope walked in. He was this younger brother full of pain. That's how he got over".

Through his suffering he developed a profound empathy for disadvantaged members of American society, which drew him into powerful connection with minority and working class communities that perhaps we have not seen since. Radical civil rights leader Sonny Carson, head of the Brooklyn CORE..."had seen the heads turn when Bobby Kennedy walked into the church: "Man it was like the Pope walked in. He was this younger brother full of pain. That's how he got over".

Bobby, more than Jack, represents promise lost for many surviving members of the generation that came of age in the 1950s and 1960s. Biographer Larry Tye, in his recently published new biography, Bobby Kennedy: The Making of a Liberal Icon, draws profound contrast between Camelot and 1968…in the place of visions of the Great Society articulated by JFK, “were cities in turmoil, whites fleeing to the suburbs as blacks vented their frustrations in the streets, and a political system unable to respond.“

He writes that Bobby “imagined a country split less between right and left, or black and white, than between good and bad. The Bobby Kennedy of 1968 was a builder of bridges - between the islands of blacks, browns, and blue-collar whites; between terrified parents and estranged youths; and between the establishment he'd grown up in and the New Politics he heralded."

In a recent panel discussion held in San Francisco, Tye and the journalist Martin Nolan reflected on the possibilities for transformational change in American society that died on the floor of the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles with Bobby Kennedy in 1968.

In the years after the chaos era, transformations did occur. Even the Chicago Daleys to a large extent repaired their connections with the black community in their city. That evolution is succinctly described in this 1999 New York Times story about the Chicago mayoral election of that year:

"In a remarkable turnaround from the bitter racial divisions here a decade ago, Mayor Richard M. Daley appears poised to win a landslide re-election victory on Tuesday with a big share of the black vote."

Mr. Daley, who took office in 1989 after the most racially polarized vote in the city's history, is winning the support of more black voters than his black challenger, Representative Bobby Rush, according to polls."

"Mr. Daley, in his first successful bid for Mayor, won less than 7 percent of the black vote. At the time many black leaders branded him a racist, an accusation that stemmed in part from bitterness toward his father, the late Richard J. Daley...In that 1989 election, one prominent black clergyman vilified Mr. Daley as "Pharaoh's son"..."

Mr. Daley's father...owed more than one early election to black support (as much as 90%). But he became estranged from the civil rights and anti-war movements in the late 1960's and early 70's."

The Irish American urban working class and the old autocratic political bosses remaining in inner cities in the 1960s and 1970s represented the tail end of many generations of pervasive Irish influence in the big cities. The nature of this power, and the personalities and perspectives of the city boss, has been ably documented in popular and historical literature, but rarely tied in to a broader, more comprehensive portrait of Irish America as a whole.

The roots of this power lie in a much harsher era, in the cities of the 19th century and the peasant roots of much of the immigrant population, with stark choices and very little support of any kind for the poor Irish immigrants beyond the institutions of their own creation.

William Kennedy wrote of Albany bosses: “Objective morality didn’t interest Albany. The Irish didn’t care about it. They understood that they had been deprived and now they were not. Now they were able to get jobs. In previous generations, when the Irish were not in power, they had not been able to get jobs. Their families starved, and starvation for them was immorality”.

The roots of this power lie in a much harsher era, in the cities of the 19th century and the peasant roots of much of the immigrant population, with stark choices and very little support of any kind for the poor Irish immigrants beyond the institutions of their own creation.

William Kennedy wrote of Albany bosses: “Objective morality didn’t interest Albany. The Irish didn’t care about it. They understood that they had been deprived and now they were not. Now they were able to get jobs. In previous generations, when the Irish were not in power, they had not been able to get jobs. Their families starved, and starvation for them was immorality”.

University of Illinois historian James Barrett describes how years of colonization taught the Irish skills to navigate the Anglo-Saxon legal and political system: “Cultural factors - especially a talent for politics ingrained in the national psyche as a result of experiences in Ireland-surely played some role in achieving Irish political influence. Likewise, territorially the network of Irish parishes resembled the city’s political districts. But many of the newer immigrants had also conducted struggles against imperial authorities. What singled out the Irish was that, having created a mass movement against British penal laws, they had developed extensive skills in negotiating complex British political and legal procedures. Their confrontation with British domination also produced in them a highly instrumental view of politics. The object, as historian Chris McNickle concluded “was to secure power by all conceivable means, hold onto it, and exploit it”. … This knowledge and language facility allowed them to serve as brokers for more recent immigrants, an edge they employed to maximize their influence. “The key to Irish American influence in the 20th century lies not in the concentrated ethnic homogeneity of their communities but rather in their presence throughout the city and in their strategies for dealing with newcomers.”

Author Tom Fleming wrote about his father Sheriff Teddy Fleming, a member of the legendary Frank Hague machine of Jersey City, New Jersey which operated an awesome level of control over that poly-ethnic blue-collar city just across the Hudson River from Manhattan from the 1920s through the 1950s.

Fleming describes the scene at his father's deathbed, where he felt he might be able to coax some reflections on a life in street politics out of the normally taciturn ward-heeler:

Fleming describes the scene at his father's deathbed, where he felt he might be able to coax some reflections on a life in street politics out of the normally taciturn ward-heeler:

“One night I tried to tell Teddy why I thought his kind of politician was important. Night after night, for thirty years, he had dealt with the thousand and one details of the Sixth Ward's voters' lives - solving quarrels between ambitious committeemen; sweet-talking dissatisfied Poles, Greeks, or Italians; getting jobs for chronic alcoholics, paroles for stickup men. I told Teddy how much I admired his patience, his steadfastness, how vital I thought it was to have men like him practicing politics on a local scale, giving the average man and woman the feeling that someone in the power structure cared about them.

My father grew more and more uncomfortable during this monologue. By the time it ended, he was looking at me as if I had gone nuts. "But Tom", he said, "You've got to listen to an awful lot of bullshit".

In these stories we find some common qualities: a keen and astute understanding of social realities, mastery of the levers of power, a genius for communication, immersion in the particularities of the lives and needs of ordinary working people, discomfort with abstraction, and sometimes a sense of strong moral purpose as provided perhaps by a Catholic education or some remnants memories of oppression.

The stories of the Irish bosses represent a very long engagement with these themes in the American city, and I think we were encountering the close of that era in chaotic years of the late Sixties and the Seventies.

The stories of the Irish bosses represent a very long engagement with these themes in the American city, and I think we were encountering the close of that era in chaotic years of the late Sixties and the Seventies.

A broader and more inclusive perspective of this era must recognize the huge Irish American role in the development and management of fundamental American institutions, legitimate and illegitimate, including social services, public and parochial education, protective services, urban inter-ethnic politics, organized crime and semi-official corruption, and the American labor movement from its very origins.

These issues are part of a much longer, interesting, and important narrative strain in American urban history. Unfortunately, the current popular notions about Irish Americans have their origins in the chaos Sixties and Seventies, just as 'the Irish' began to fade away as a cohesive, easily identifiable urban community, and the remnant communities presented a kind of retrograde reactionary face to the zeitgeist. Fortunately we have living accounts of the characters and personalities who took leading roles in that era on all sides of the equation, diluting the argument that Irish-Americans were intrinsically disposed to reactionary politics and racism.

My hope is that this line of inquiry, inclusive of the broader range of historical experience and taking into account the full range of stories, will force through a more sustainable view of certain persistent types and continuities in the Irish American experience, beyond a reductive, simplistic, and baldly prejudicial left/right narrative.

My hope is that this line of inquiry, inclusive of the broader range of historical experience and taking into account the full range of stories, will force through a more sustainable view of certain persistent types and continuities in the Irish American experience, beyond a reductive, simplistic, and baldly prejudicial left/right narrative.

Copyright 2019 Anthony Bucher - All Rights Reserved

ISHMAEL REED ARTICLE HERE

APRIL 7, 2008

The Irish Black Thing

by ISHMAEL REED FacebookTwitterRedditEmail

When the media probe the homicides resulting from gang wars, taking place in my Oakland neighborhood, they call upon the two or three African Americans listed on their Rolodexes to comment. Most of them live in places like Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Similarly, those on cable, who are commenting about how the “white working class,” or “Reagan democrats” are going to vote in Pennsylvania are as distant from “the white working class” as those Harvard experts are distant from the lives of those who live in neighborhoods like mine.

From the way they behave as experts on the “blue collar workers,” however, you’d think that they brown-bagged peanut butter and jelly sandwiches to work instead of dining in some of the most exclusive restaurants in New York and Washington, often with the people whom they cover. That they motor to work in used Chevys instead of being chauffeur-driven in network limousine services.

Columnist Maureen Dowd identified the ethnics who are referred to in euphemistic phrases. She said that they were members of her tribe, the Irish (Times, 3/19/08), who are opposing Barack Obama’s steady march toward the Democratic nomination, ignoring the fact that hundreds of thousands of Irish Americans have probably already voted for the senator. As Dan Cassidy, author of CounterPunch Books’ How The Irish Invented Slang emailed me

“The [Rev]. Wright pseudo-flap sure isn’t keeping mainstream Dem. Micks from endorsing Obama in slews, ie Bob Casey other day, Pat Leahy, Teddy Kennedy, Caroline Kennedy, Patrick K., etc. I was with a slew of writers from Bill Kennedy to Dan Barry at NYT, TJ English, Peter Quinn, Terry Golway, etc ets & all are for Obama.”

Although there are many progressive Irish Americans like Cassidy, the media profile of Irish America lies somewhere between shrill talk-show hosts, who yell and interrupt their guests or a snarling resentful Archie Bunker types, or Bernard McQuirk ,whose comment about the Rutgers basketball team led to Don Imus’s firing, or a pugnacious Pat Buchanan who believes that it was Grant who surrendered at Appomattox.

In the movies it’s “Dirty Harry Callahan” who violates the constitutional rights of suspects.

There seems to be no place for a Pat Goggins of the San Francisco United Irish Cultural Center, or authors Bob Callahan and Dan Cassidy, who have worked for decades to heal whatever divisions exist between African Americans and Irish Americans.

When a memorial was held for Callahan in Berkeley, a few weeks ago, there were African Americans in attendance including Al Young, the poet laureate of California, and Joyce Carol Thomas, winner of a National Book Award. Callahan not only counted friends in the African-American community but Native American and Hispanic communities as well. He’s the one who put me in touch with Andy Hope, poet of the Tlingit tribe, a relationship that led to my partner, Carla Blank, and I to being made honorary Klan members on September 26, 1998, during an all day potlatch held in Sitka, Alaska.

When I told a professor at an eastern college that my mother and grandmother claimed Irish ancestry, he laughed. Since the Irish were indentured servants working on the same plantations as African Americans, why should it be a surprise that hundreds of thousands of African Americans are members of the Celtic Diaspora as well as the African Diaspora? Gerry Adams, of Sinn Fein, cited this plantation experience when lecturing to students at the University of California at Berkeley.

He said that it was the plantation owners who created whiteness as a standard. They wanted to separate the two groups. Some of those Irish men who left Ireland during the potato famine married African-American women, and as Noel Ignatiev points out in his book, How The Irish Became White, Irish American women married African American men. He writes,

“In New York, the majority of cases of ‘mixed’ matings involving Irish women.The same was true in Boston. A list of employees of the Narragansett and National Brick company in 1850 includes a number described as of Irish nationality who are also listed as “mulattoes.”

In the 1860s, Muhammad Ali’s great great grandfather, Abe Grady, came from Ireland. If Alex Haley had done a “Roots” about tracing his father’s ancestry it would have taken him twelve generations into Ireland. Isn’t it odd that so called Reagan democrats — Dowd’s Irish –e would be opposed to Obama. His mother was Irish, a descendant of Falmouth Kearney, who arrived in New York in 1850, a fact never mentioned when the cable guys are exhibiting their expertise about bowling and beer guzzling.

As the late John Mohar of the Delancey Street Foundation said, when introducing me at a dinner held by the Celtic Foundation, if one drop of black blood makes you black- a commercial definition created by those for whom human beings were assets like cattle — why doesn’t one drop of Irish blood make you Irish?

The cotton planter’s one-drop rule shows little change in racial definitions since the medieval notion that the child of a black and white relationship would be polka dot.

American scientists may be able to analyze the chemical composition of one of Saturn’s moons, but when it comes to race ,the national discussion is back in the stone age. Some of our leading public intellectuals sound like Fred Flinstones when discussing the issue. Callahan knew his way around this and other topics, because he did his homework. In the material distributed during his memorial service held at Anna’s Jazz Island in Berkeley, Robert Owen Callahan was described as “Gifted with a silver tongue, rapid-fire synaptic flashes and a huge store of talk, he was unabashed in his enthusiasms, embracing the best of both the schlock and the sublime of American culture and with a characteristic Callahan zeal.”

He had a gargantuan intellectual appetite. (He could eat, too!)He was a genius. He had a mind that roamed over a number of fields of interests, from ecology, archeology, anthropology, botany, the Native American oral tradition to comics.

He edited The New Smithsonian Book Of Comic Book Stories. He wrote the narrative for the famous graphics novel, “The Dark Hotel,” illustrated by the great cartoonist, Spain Rodriguez. It was a cult classic. He was also a publisher.

I introduced Callahan to Zora Neale Hurston. He was responsible for republishing some of her books, including her masterpiece, Tell My Horse. At the time of his death, he was working with Joyce Carol Thomas on a graphics novel based upon Zora Neale Hurston’s work. We both took tenuous steps into each other’s world. When Callahan invited me to a dinner held by the Irish Cultural Center I called him several times during the day to seek his assurance that I wouldn’t be harmed. I was treated very well, and my presence was even announced from the stage. On the night of the Holmes-Cooney fight, Callahan his son David and I went to the Oakland auditorium to watch it on the big screen. While David, who was a youngster at the time, mingled with the crowd, Callahan, seeing that he and David were the only whites in attendance, looked around and said, “I hope that Cooney loses.”

While the Irish and Blacks have clashed in street riots, there have also been instances where the blacks and Irish joined in rebellion. On the evening of March 5, 1770, Crispus Attucks, an African American was in the front lines of a group of thirty to sixty Americans who clashed with the British, resulting in the Boston Massacre. Behind Attucks were those described by John Adams, who represented the British Soldiers, in court, as “a motley rabble of saucy boys, negroes and mulattoes, Irish teagues and outlandish jack tarrs”.

The result of this confrontation was the Boston Massacre. In 1741 a group consisting of Irish and blacks engaged in a “plot to burn New York and murder its inhabitants.” The leader, a slave named Ceasar, Peggy Kerry and a catholic priest named John Ur were executed.

John F.Kennedy, in the minds of some, did more to advance the Civil Rights movement than any president in history, publicly as well as privately. When I visited the black employees at Lockheed Martin in February, I was informed that Kennedy threatened to withhold federal funds unless Lockheed integrated its lunch rooms. Maybe that’s why, according to Abraham Bolden, author of The Echo from Dealy Plaza, some white secret service men called Kennedy “a nigger lover,” and vowed never to take a bullet for the president. Both Callahan and I were Kennedy admirers; Callahan was co-author of Who Shot JFK?.

We listened to each other and learned from each other. It was Callahan who selected some New York Irish American intellectuals to lecture at the Studio Museum in Harlem.

Such inter ethnic communication is far more useful than cable shows pitting one group against another in an effort to raise ratings. No one denies that a racial divide exists in the country; the media exacerbate it for money. That’s been the American media’s mission for over two hundred years. A number of those murderous riots during which the Irish and blacks clashed were inflamed by a yellow press.

Callahan taught me a lot about myself and about the history of white ethnics something that my formal education neglected to cover. In the school books as well as in the media, we’re either blacks or whites. The whites are always San Antonio, and blacks are always the Knicks.

Callahan was a white man who listened. Though he would object to such a designation. Callahan, editor of “Callahan’s Irish Quarterly, “and author of The Big Book Of Irish-American Culture was most of all an Irish American.

We got along with Callahan because unlike many “whites,” he never forgot where he came from. He never forgot his roots.

[Note: In 2007 the magazine Irish America voted Dan Cassidy one its 100 top Irish Americans in that year. The same magazine similarly honored CounterPunch coeditor Alexander Cockburn in 1992. Editors.]

ISHMAEL REED is a poet, novelist and essayist who lives in Oakland. His widely-accalimed novels include, Mumbo Jumbo, the Freelance Pallbearers and the Last Days of Louisiana Red. He has recently published a fantastic book on Oakland: Blues City: a Walk in Oakland and Carroll and Graf has recently published a thick volume of his poems: New and Collected Poems: 1964-2006.

He is also the editor of the online zine Konch.

Copyright 2008 ISHMAEL REED

APRIL 7, 2008

The Irish Black Thing

by ISHMAEL REED FacebookTwitterRedditEmail

When the media probe the homicides resulting from gang wars, taking place in my Oakland neighborhood, they call upon the two or three African Americans listed on their Rolodexes to comment. Most of them live in places like Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Similarly, those on cable, who are commenting about how the “white working class,” or “Reagan democrats” are going to vote in Pennsylvania are as distant from “the white working class” as those Harvard experts are distant from the lives of those who live in neighborhoods like mine.

From the way they behave as experts on the “blue collar workers,” however, you’d think that they brown-bagged peanut butter and jelly sandwiches to work instead of dining in some of the most exclusive restaurants in New York and Washington, often with the people whom they cover. That they motor to work in used Chevys instead of being chauffeur-driven in network limousine services.

Columnist Maureen Dowd identified the ethnics who are referred to in euphemistic phrases. She said that they were members of her tribe, the Irish (Times, 3/19/08), who are opposing Barack Obama’s steady march toward the Democratic nomination, ignoring the fact that hundreds of thousands of Irish Americans have probably already voted for the senator. As Dan Cassidy, author of CounterPunch Books’ How The Irish Invented Slang emailed me

“The [Rev]. Wright pseudo-flap sure isn’t keeping mainstream Dem. Micks from endorsing Obama in slews, ie Bob Casey other day, Pat Leahy, Teddy Kennedy, Caroline Kennedy, Patrick K., etc. I was with a slew of writers from Bill Kennedy to Dan Barry at NYT, TJ English, Peter Quinn, Terry Golway, etc ets & all are for Obama.”

Although there are many progressive Irish Americans like Cassidy, the media profile of Irish America lies somewhere between shrill talk-show hosts, who yell and interrupt their guests or a snarling resentful Archie Bunker types, or Bernard McQuirk ,whose comment about the Rutgers basketball team led to Don Imus’s firing, or a pugnacious Pat Buchanan who believes that it was Grant who surrendered at Appomattox.

In the movies it’s “Dirty Harry Callahan” who violates the constitutional rights of suspects.

There seems to be no place for a Pat Goggins of the San Francisco United Irish Cultural Center, or authors Bob Callahan and Dan Cassidy, who have worked for decades to heal whatever divisions exist between African Americans and Irish Americans.

When a memorial was held for Callahan in Berkeley, a few weeks ago, there were African Americans in attendance including Al Young, the poet laureate of California, and Joyce Carol Thomas, winner of a National Book Award. Callahan not only counted friends in the African-American community but Native American and Hispanic communities as well. He’s the one who put me in touch with Andy Hope, poet of the Tlingit tribe, a relationship that led to my partner, Carla Blank, and I to being made honorary Klan members on September 26, 1998, during an all day potlatch held in Sitka, Alaska.

When I told a professor at an eastern college that my mother and grandmother claimed Irish ancestry, he laughed. Since the Irish were indentured servants working on the same plantations as African Americans, why should it be a surprise that hundreds of thousands of African Americans are members of the Celtic Diaspora as well as the African Diaspora? Gerry Adams, of Sinn Fein, cited this plantation experience when lecturing to students at the University of California at Berkeley.

He said that it was the plantation owners who created whiteness as a standard. They wanted to separate the two groups. Some of those Irish men who left Ireland during the potato famine married African-American women, and as Noel Ignatiev points out in his book, How The Irish Became White, Irish American women married African American men. He writes,

“In New York, the majority of cases of ‘mixed’ matings involving Irish women.The same was true in Boston. A list of employees of the Narragansett and National Brick company in 1850 includes a number described as of Irish nationality who are also listed as “mulattoes.”

In the 1860s, Muhammad Ali’s great great grandfather, Abe Grady, came from Ireland. If Alex Haley had done a “Roots” about tracing his father’s ancestry it would have taken him twelve generations into Ireland. Isn’t it odd that so called Reagan democrats — Dowd’s Irish –e would be opposed to Obama. His mother was Irish, a descendant of Falmouth Kearney, who arrived in New York in 1850, a fact never mentioned when the cable guys are exhibiting their expertise about bowling and beer guzzling.

As the late John Mohar of the Delancey Street Foundation said, when introducing me at a dinner held by the Celtic Foundation, if one drop of black blood makes you black- a commercial definition created by those for whom human beings were assets like cattle — why doesn’t one drop of Irish blood make you Irish?

The cotton planter’s one-drop rule shows little change in racial definitions since the medieval notion that the child of a black and white relationship would be polka dot.

American scientists may be able to analyze the chemical composition of one of Saturn’s moons, but when it comes to race ,the national discussion is back in the stone age. Some of our leading public intellectuals sound like Fred Flinstones when discussing the issue. Callahan knew his way around this and other topics, because he did his homework. In the material distributed during his memorial service held at Anna’s Jazz Island in Berkeley, Robert Owen Callahan was described as “Gifted with a silver tongue, rapid-fire synaptic flashes and a huge store of talk, he was unabashed in his enthusiasms, embracing the best of both the schlock and the sublime of American culture and with a characteristic Callahan zeal.”

He had a gargantuan intellectual appetite. (He could eat, too!)He was a genius. He had a mind that roamed over a number of fields of interests, from ecology, archeology, anthropology, botany, the Native American oral tradition to comics.

He edited The New Smithsonian Book Of Comic Book Stories. He wrote the narrative for the famous graphics novel, “The Dark Hotel,” illustrated by the great cartoonist, Spain Rodriguez. It was a cult classic. He was also a publisher.

I introduced Callahan to Zora Neale Hurston. He was responsible for republishing some of her books, including her masterpiece, Tell My Horse. At the time of his death, he was working with Joyce Carol Thomas on a graphics novel based upon Zora Neale Hurston’s work. We both took tenuous steps into each other’s world. When Callahan invited me to a dinner held by the Irish Cultural Center I called him several times during the day to seek his assurance that I wouldn’t be harmed. I was treated very well, and my presence was even announced from the stage. On the night of the Holmes-Cooney fight, Callahan his son David and I went to the Oakland auditorium to watch it on the big screen. While David, who was a youngster at the time, mingled with the crowd, Callahan, seeing that he and David were the only whites in attendance, looked around and said, “I hope that Cooney loses.”

While the Irish and Blacks have clashed in street riots, there have also been instances where the blacks and Irish joined in rebellion. On the evening of March 5, 1770, Crispus Attucks, an African American was in the front lines of a group of thirty to sixty Americans who clashed with the British, resulting in the Boston Massacre. Behind Attucks were those described by John Adams, who represented the British Soldiers, in court, as “a motley rabble of saucy boys, negroes and mulattoes, Irish teagues and outlandish jack tarrs”.

The result of this confrontation was the Boston Massacre. In 1741 a group consisting of Irish and blacks engaged in a “plot to burn New York and murder its inhabitants.” The leader, a slave named Ceasar, Peggy Kerry and a catholic priest named John Ur were executed.

John F.Kennedy, in the minds of some, did more to advance the Civil Rights movement than any president in history, publicly as well as privately. When I visited the black employees at Lockheed Martin in February, I was informed that Kennedy threatened to withhold federal funds unless Lockheed integrated its lunch rooms. Maybe that’s why, according to Abraham Bolden, author of The Echo from Dealy Plaza, some white secret service men called Kennedy “a nigger lover,” and vowed never to take a bullet for the president. Both Callahan and I were Kennedy admirers; Callahan was co-author of Who Shot JFK?.

We listened to each other and learned from each other. It was Callahan who selected some New York Irish American intellectuals to lecture at the Studio Museum in Harlem.

Such inter ethnic communication is far more useful than cable shows pitting one group against another in an effort to raise ratings. No one denies that a racial divide exists in the country; the media exacerbate it for money. That’s been the American media’s mission for over two hundred years. A number of those murderous riots during which the Irish and blacks clashed were inflamed by a yellow press.

Callahan taught me a lot about myself and about the history of white ethnics something that my formal education neglected to cover. In the school books as well as in the media, we’re either blacks or whites. The whites are always San Antonio, and blacks are always the Knicks.

Callahan was a white man who listened. Though he would object to such a designation. Callahan, editor of “Callahan’s Irish Quarterly, “and author of The Big Book Of Irish-American Culture was most of all an Irish American.

We got along with Callahan because unlike many “whites,” he never forgot where he came from. He never forgot his roots.

[Note: In 2007 the magazine Irish America voted Dan Cassidy one its 100 top Irish Americans in that year. The same magazine similarly honored CounterPunch coeditor Alexander Cockburn in 1992. Editors.]

ISHMAEL REED is a poet, novelist and essayist who lives in Oakland. His widely-accalimed novels include, Mumbo Jumbo, the Freelance Pallbearers and the Last Days of Louisiana Red. He has recently published a fantastic book on Oakland: Blues City: a Walk in Oakland and Carroll and Graf has recently published a thick volume of his poems: New and Collected Poems: 1964-2006.

He is also the editor of the online zine Konch.

Copyright 2008 ISHMAEL REED

Comments

Post a Comment